- Home

- Gary J. Bass

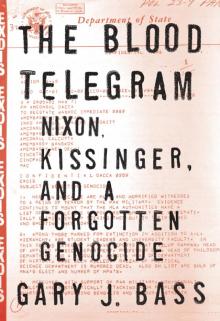

The Blood Telegram Page 6

The Blood Telegram Read online

Page 6

Galvanized by their triumph, Mujib and the Awami League had to make good on their campaign for autonomy for the Bengalis. Showing his popular strength, Mujib called a huge rally, where he pleaded with the rapturous crowd to carry on if he was assassinated. As Yahya, Mujib, and Bhutto began negotiating about the future of the country, Blood still hoped to avoid violence. He believed that Mujib was not aiming for secession except as a desperate last resort. “My thinking was that the Awami League platform was a recipe for the dissolution of Pakistan,” he said later, “but it could be a recipe for the peaceful dissolution of Pakistan.”40

This was a moment when the United States might have stood on principle. There had been a free and fair election, truly expressive of the will of the people. The democratic superpower could have encouraged Pakistan to deepen its democratic traditions. “We are the great democracy,” says Meg Blood. “And here was a democratic game being played, as if they would pay any attention once Mujib had won. They were prepared to simply push him aside.” She adds, “We, the great American nation, leaned back and said nothing.”41

The White House took almost no interest in upholding the results of Pakistan’s grand experiment in democracy. Instead, the Nixon team dreaded the loss of its Cold War ally. The State Department unhappily thought that Pakistan was likely to crack apart. Kissinger asked Nixon whether the United States should be warming up to Mujib, who was friendly to the country. But Nixon, sticking with Yahya, scrawled, “not yet” and “not any position which encourages secession.”42

Harold Saunders, the White House senior aide for South Asia, braced Kissinger for the prospect of another partition. Expecting East Pakistan to secede, he asked Kissinger how hard the United States should work to avoid bloodshed. They were, he wrote, “witnessing the possible birth of a new nation of over 70 million people.… [W]e could have something to do with how this comes about—peacefully or by bloody civil war.”43

A protracted series of negotiations between Yahya, Bhutto, and Mujib amounted to nothing. “Mujib has let me down,” Yahya bitterly told one of his ministers. “I was wrong in trusting this person.” On March 1, under pressure from Bhutto, Yahya indefinitely postponed the opening of the National Assembly, which had been scheduled for March 3. To the Bengalis who had decisively voted for the Awami League, this looked like outright electoral theft. Yahya, wiping away the democratic election that he had allowed, declared that Pakistan was facing its “gravest political crisis.”44

When Blood heard the news of the postponement on the radio, he dashed up to the roof of the Adamjee Court building. “We could see Bengalis pouring out of office buildings all around that neighborhood,” he remembered. “Angry as hornets.” They were screaming in rage. They had believed Yahya, he thought, and now were being robbed of their democratic victory. Although the crowds stayed peaceful, many people were carrying clubs or lathis (long wooden staffs, a weapon of choice for police in the subcontinent). He told the State Department, “I’ve seen the beginning of the breakup of Pakistan.”45

Scott Butcher, the young political officer, remembers a wave of civil disobedience, with outraged crowds in the streets and a number of clashes with the Pakistani authorities. The next day, Bengalis launched a general strike, in the storied tradition of mass mobilizations against the British Empire. This showed the generals who really ran East Pakistan. At Mujib’s word, normal life came to a halt. The shops were shuttered, and neither cars nor bicycles were allowed on the streets, which instead were filled with Bengalis chatting and wandering around. Bands of youths roved the city, shouting, “Joi Bangla!”—victory to Bengal.46

Catastrophe loomed. Blood worried at incidents of arson and looting, and ugly acts of intimidation of West Pakistanis. There were some small but potentially disastrous skirmishes with the army, which was out in full force. Mujib called for disciplined and peaceful mobilization of his followers. “I thought that the situation was intolerable to the army,” says Griffel. “The solemnness of the population, the mild violence, the civil disobedience, the constant strikes, the university students—I don’t think that was tolerable for long.”47

Butcher was impressed by the military’s restraint, which he found remarkable: “They were being spat upon, harassed and hassled by locals, but behaving quite well under the circumstances.” Yahya broadcast an angry speech to the nation on March 6, accusing the “forces of disorder” of engaging in looting, arson, and killing. Under pressure from these mass demonstrations, he announced that the new National Assembly would now open on March 25. But with the politicians still deadlocked, Yahya threatened the worst: “It is the duty of the Pakistan armed forces to insure the integrity, solidarity, and security of Pakistan, and in this they have never failed.”48

“THE RESULT WOULD BE A BLOOD-BATH”

The only possible hope was to avoid a military crackdown. Once the shooting started, the Bengalis would be radicalized; the military’s prestige would be engaged; the violence could escalate into civil war. The whole region might plunge into chaos. In the last days before Yahya fired his fateful first shots, the United States did not exert itself to prevent that doom.

There was plenty of warning. Kissinger was alerted that, according to Blood’s consulate, there was almost no chance of Pakistan holding together. But Nixon put his trust in Yahya. “I feel that anything that can be done to maintain Pakistan as a viable country is extremely important,” he said. “They’re a good people. Strong. People like Yahya are responsible leaders.” Soon after, when Kissinger mentioned there was a problem coming with the separation of East Pakistan, the president was surprised: “They want to be separated?”49

Kissinger might breeze past advice from Blood and the distrusted State Department, but it was much harder to ignore similar alarms from his own handpicked White House staff. Samuel Hoskinson, who knew more about South Asia than anyone else in the White House, warned of a looming civil war that Yahya’s government would probably lose. He recalled the recent horrors of the attempt by the Biafrans to secede from Nigeria. He suggested that Pakistan would be better off with a confederal system, giving East Pakistan under Mujib the maximum amount of autonomy short of secession. “It was not the popular thing to say,” Hoskinson remembers. “We had some concern what kind of blowback we would get from Henry, which could be pretty bad.” But he says, “He didn’t blow up on me. Not that time.”50

Harold Saunders was quieter and impeccably polite, but on March 5 he warned Kissinger that the Pakistan army was probably preparing to launch a futile crackdown. There was still a last chance to avoid slaughter by leaning hard on Yahya. Saunders recommended a government report that argued for threatening to stop economic aid to Pakistan to prevent bloodshed. He emphasized the crucial decision: “The tough question is whether to make a major effort to stop West Pakistani military intervention.”51

The next day, Kissinger convened one of his frequent meetings in the White House Situation Room, gathering senior officials from the State Department, Pentagon, and CIA. It was the last high-level overview of U.S. policy before Yahya began his killing spree—a final opportunity for the United States to use its considerable influence to dissuade its ally from violence. A senior State Department official warned, “The judgment of all of us is that with the number of troops available to Yahya (a total of 20,000, with 12,000 combat troops) and a hostile East Pakistan population of 75 million, the result would be a blood-bath with no hope of West Pakistan reestablishing control over East Pakistan.” Another senior official warned of a possible “real blood-bath … comparable to the Biafra situation.”

Kissinger seemed convinced at first. “I agree that force won’t work,” he said. But when a State Department official argued that the United States should discourage Yahya from shooting, Kissinger dug in his heels. “If I may be the devil’s advocate,” he asked, “why should we say anything?” He asked warily, “What would we do to discourage the use of force? Tell Yahya we don’t favor it?” Kissinger said firmly, “Intervention wou

ld almost certainly be self-defeating.” He invoked Nixon’s friendship with Yahya: “The President will be very reluctant to do anything that Yahya could interpret as a personal affront.” He was skeptical of even the gentlest U.S. warnings: “If we could go in mildly as a friend to say we think it’s a bad idea, it wouldn’t be so bad. But if the country is breaking up, they won’t be likely to receive such a message calmly.” He said, “In the highly emotional atmosphere of West Pakistan under the circumstances, I wonder whether sending the American Ambassador in to argue against moving doesn’t buy us the worst of everything. Will our doing so make the slightest difference? I can’t imagine that they give a damn what we think.” The group, following Kissinger, settled on what a State Department official called “massive inaction.”52

Harold Saunders remembers that “there was a principle in their minds, which could be intellectually justified, although maybe not in practical terms: we’re not going to tell someone else how to run his country.” This was, he adds, the same tenet used for the shah of Iran. “I think it was the wrong principle myself,” he says. “I heard it articulated by Henry on a number of occasions.”53

Kissinger’s decision stuck. He seemed more influenced by warnings that many West Pakistanis suspected that the United States was plotting to split up the country. The State Department instructed Blood not to try to dissuade Yahya from shooting.54

On March 13, Kissinger sent Nixon what would turn out to be his final word on Pakistan before the killing started. Kissinger made “the case for inaction.”55

He correctly warned that Yahya and the Pakistani military seemed “determined to maintain a unified Pakistan by force if necessary.” And he noted that a crackdown might not succeed: “[Mujib] Rahman has embarked on a Gandhian-type non-violent non-cooperation campaign which makes it harder to justify repression; and … the West Pakistanis lack the military capacity to put down a full scale revolt over a long period.”

But Kissinger urged the president to do nothing. He wrote that the U.S. government’s consensus—forged by him—was that “the best posture was to remain inactive and do nothing that Yahya might find objectionable.” Kissinger did not want to caution Yahya against opening fire on his people, ruling out “weighing in now with Yahya in an effort to prevent the possible outbreak of a bloody civil war.” It was “undesirable” to speak up, because “we could realistically have little influence on the situation and anything we might do could be resented by the West Pakistanis as unwarranted interference and jeopardize our future relations.” Kissinger preferred to stick with Yahya: “it is a more defensible position to operate as if the country remains united than to take any move that would appear to encourage separation. I know you share that view.”56

There was one consideration that, while voiced by other U.S. officials, never made it into Kissinger’s note to the president: simply avoiding the loss of life. The last chance of maintaining a united Pakistan would have been warning Yahya that force—especially brutal force—would be disastrous and have consequences for Pakistan’s relationship with the United States. Just two weeks after the slaughter began, Kissinger would say that if the United States had had a choice on March 25, it would have urged Yahya not to use force. He was already covering up the fact that the Nixon administration had had many opportunities to make such requests to Yahya, and had expressly chosen silence.57

East Pakistan teetered on the verge of anarchy. With the days dwindling until the fateful March 25 deadline for opening the National Assembly, the three main Pakistani leaders kept on bargaining, but with frighteningly few signs of a political breakthrough. Bhutto insisted that his party, dominant in West Pakistan, should take a big role in any new government, and that Pakistan could not be allowed to disintegrate.58

Mujib, at another huge rally of half a million people—many of them carrying iron rods and bamboo sticks—held back from declaring an independent Bangladesh, but demanded that the army withdraw to its barracks and yield power to the winners of the election. “It was a vast number of people who had suddenly become political,” says Meg Blood. “They had been insulted because their vote had been ignored.” The Pakistani security forces found themselves overwhelmed by an uprising that roiled throughout Dacca, Chittagong, Jessore, and elsewhere. The Pakistani martial law administration admitted that 172 people had been killed in the first week of March—figures they had to put out to debunk stories among livid Bengalis that hundreds or thousands had been killed. Archer Blood found the military’s statement “reasonable, almost apologetic in tone, and seemingly honest.”59

Ominously, Pakistan flew in more and more troops, who landed from West Pakistan at the Dacca airport. The airport became an armed fort, bristling with dug-in automatic antiaircraft weapons and gun emplacements. Several times in March, Blood watched about a hundred young men debarking from a Pakistan International Airlines plane, all of them dressed alike in neat short-sleeved white shirts and chino trousers. They lined up and marched off smartly. Yahya shoved aside the moderate general who had been governor of East Pakistan, terrifying Bengalis with his replacement: Lieutenant General Tikka Khan, known widely as “the butcher of Baluchistan” for his devastating repression of an uprising in that West Pakistani province. Blood knew he was one of the most extreme hawks in the military—a killer.60

Blood still did not quite see the massacres coming. He was relieved that Mujib had chosen to avoid declaring independence, and predicted an “essentially static waiting game” as Bengali crowds faced off against the army. (He would later be ashamed of his assessment.) He knew that Bengali nationalists would not be cowed by a whiff of grapeshot, and could not believe that Pakistan’s generals would be stupid enough to try it.61

Blood was anything but an Awami League partisan. He saw Mujib as principled but exasperatingly obdurate, and warned the League that Yahya and his prideful senior officers had been restrained in the face of considerable provocation. Afterward, he would disgustedly condemn Mujib for overreaching. The nationalist leader had been swept away by the spectacle of “tens of thousands of militant people, men, women and children of all classes thronged by the sheikh’s house chanting slogans” about the “ ‘emancipation’ of Bangla Desh.” (The name is Bengali for “Bengal Nation.”) The U.S. consul was baffled by “the mystic belief that essentially unarmed masses could triumph in test of wills with martial law government backed by professional army.”62

Still, Blood admired the Bengali nationalist crowds. Swept up in their effusive mood, he confessed in a cable “a certain lack of objectivity. It is difficult to be completely objective in Dacca in March 1971 when, out of discretion rather than valor, our cars and residences sport black flags and we echo smiling greetings of ‘Joi Bangla’ as we move about the streets.” He enthused, “Daily we lend our ears to the out-pouring of the Bengali dream, a touching admixture of bravado, wishful thinking, idealism, animal cunning, anger, and patriotic fervor. We hear on Radio Dacca and see on Dacca TV the impressive blossoming of Bengali nationalism and we watch the pitiful attempts of students and workers to play at soldiering.”

But his zest was tempered with growing dread. He came to realize how this would probably end. He hoped the army would follow logic rather than emotion. Blood, whose pragmatism outweighed his Bengali sympathies, evenhandedly hoped for a political “solution which will give something to Bhutto, something to Mujib, something to Yahya and the army, still preserve at least a vestige of the unity of Pakistan, and hopefully buy time for a cooling of passions.”63

The best prospect would be a confederation, with Yahya as president of both wings, Bhutto as prime minister of West Pakistan, and Mujib as “prime minister of Bangla Desh (East Pakistan has become a term for geographers).” Mujib could not compromise on his promises of autonomy; his people would never accept that now. But autonomy came dangerously close to independence for Bangladesh, and Blood thought that Yahya would likely balk. He presciently wrote, “The ominous prospect of a military crackdown is much more than a

possibility, but it would only delay, and ensure, the independence of Bangla Desh.” Blood suggested telling Yahya that the United States wanted a political solution, but the State Department—following Kissinger’s guidance—maintained its silence.64

Dacca became a more menacing place for Americans. The CIA warned Blood that communists were trying to assassinate him. Late one night, three Urdu-speaking men in a car without a license plate drove up to the Adamjee Court building that housed the consulate, threw two handmade bombs, and fired a revolver into the air. The building shook. A few nights later, Archer and Meg Blood heard several gunshots at their house. Someone in a jeep had driven up to the consul’s residence, fired three shots, and raced off. Meg Blood remembers suspicions fell on the Naxalites, the Maoist revolutionaries: “They thought it would be a nice chaotic thing to assassinate the man in charge.” The Bloods found bullet holes in the veranda off their bedroom. The U.S. consulate and other American buildings in Dacca faced regular bombings with Molotov cocktails, which were nerve-jangling but so far mercifully amateurish. After two Molotov cocktails were thrown at American business offices in downtown Dacca, Archer Blood shrugged it off: “Bombing gang still active and happily still ineffective.”65

On March 15—which Blood bookishly noted was the Ides of March—Yahya arrived in Dacca for more negotiations. It was, one of Yahya’s ministers despairingly recalled, “like giving oxygen to a dying patient when the doctors have declared him a lost case.” Blood suffered a moment of optimism. “Things are looking up,” he reported after talks between Yahya and Mujib. The same day that he wrote that, there was a serious clash twenty miles north of Dacca, as Pakistani troops opened fire when they were stopped by a furious crowd, killing at least two civilians. Mujib privately passed along a message to Blood that these provocations made it hard to sell a peace deal to his own people. Blood, having none of it, sent to Mujib “the natural rejoinders: rise above the matter; play the statesman; surely Yahya must be as unhappy about such incidents as Mujib.”66

The Blood Telegram

The Blood Telegram