- Home

- Gary J. Bass

The Blood Telegram Page 34

The Blood Telegram Read online

Page 34

Nixon did write to Yahya that it would be “helpful” for him to enlist the elected Bengali politicians for national reconciliation, and later added that he was sure that Yahya wanted “maximum” participation of the Bengalis’ elected representatives. Yahya, having done his worst, had seemingly moved into the mopping-up phase of the crackdown, and professed a greater willingness to consider political accommodation. But Kissinger’s own aides called Yahya’s political efforts inadequate and “vacuous.” Yahya moved frustratingly slowly in planning for a new East Pakistan government, while refusing to lift the ban on the Awami League or to make serious efforts to deal with the victors of the election. The White House staff noted that “the army will try 45% of its elected representatives.” Kissinger still hoped to hold Pakistan together with autonomy for East Pakistan, but without a deal with legitimate Bengali leaders, there was little chance of any lasting peace there.44

Yahya said that he would welcome a secret meeting between Pakistani officials and Bengali politicians who accepted a unified Pakistan. The White House searched in vain for influential Awami League representatives who would settle for less than independence, but went no further than that, not wanting to mediate. The U.S. consul in Calcutta was authorized to tell the Bangladeshi exile government based there that Yahya was interested in talks. But the Bangladeshi leadership insisted that only Mujib could speak for them, and Kissinger complained that they wanted unconditional independence, which put an end to any possible negotiations. As for Yahya freeing Mujib and negotiating with him, Kissinger said, “I think that’s inconceivable! Unless Yahya’s personality has changed 100% since I saw him in July.”45

With no political deal in sight, U.S. diplomats in Pakistan painted a bleak picture. Few Bengalis believed in the declared amnesty, as arrests continued and few prominent people were released. The civilian governor seemed obviously a cat’s paw of the martial law authorities. Whatever good had been done by removing Tikka Khan, argued the second-ranked U.S. official in Islamabad, it was undercut by continuing army reprisals against the population. As the CIA noted, martial law continued: “Any civilian government established in East Pakistan under the army’s aegis is likely to be more shadow than substance.”46

Yahya’s steps were welcome, but from the viewpoint of skeptical U.S. officials in Washington and Delhi, the White House’s successes gave a small but tantalizing preview of what might have been possible if the United States had tried harder to use its leverage in a serious way from the start. From India’s perspective, Yahya was trimming his sails out of fear of an Indian attack. As much as Nixon and Kissinger would later brag about these achievements, at this late date they unfortunately mattered little.

Trapped in a desk job in the State Department bureaucracy, Archer Blood was doing his best to endure his ouster from the Dacca consulate with a stiff upper lip. While he was usually in no position to remind his bosses that he had told them so, the ex-consul’s prognostications in his cables were being confirmed by events. He once managed to get a half-hour meeting with the second-ranked official at the State Department, and declared confidently that the Bengalis, helped by Indian intervention, would eventually win their struggle. Their escalating guerrilla campaign, he said, was bleeding Pakistan white. The independent Bangladesh that he had predicted was well on the way to becoming a reality. “My husband had a different, long view,” remembers Meg Blood. “He could see it was not going to simmer down or go away.”47

As Indira Gandhi’s trip to Washington approached, Nixon’s policy seemed to the Indians to be almost completely one-sided. As an Indian diplomat scornfully noted, the Nixon administration’s real policy was to treat the issue as an internal matter for Pakistan, give as much diplomatic and economic aid to Pakistan as possible, try to keep up arms supplies to Pakistan, and not condemn Pakistan’s atrocities. This was leavened only by relief assistance to India for the refugees, which had been “played up out of all proportion to its quantum.”48

India, dismissing Yahya as “looking for quislings,” argued that Pakistan had to negotiate with Mujib himself. Haksar did not see how there could be any viable political deal without the overwhelming democratic choice of the Bengalis. When William Rogers, the secretary of state, said that the Americans could not force Yahya to talk to a man he saw as a traitor, Haksar retorted, “Churchill said worse things about Gandhi.” Haksar told Rogers, “The British talked to Gandhi and Nehru, … but Yahya Khan is not willing to talk with Mujibur Rahman.”49

Nor was India especially impressed with U.S. aid to the refugees—even before the Nixon administration started threatening to cut off foreign aid, a blow that would more than cancel out prior U.S. donations for the refugees. India saw the refugees as a symptom, not the disease, and anyway thought that the symptom was going almost entirely untreated.

It was true that, as the White House privately reckoned, the United States had provided a substantial $89 million, and other foreign governments had scraped together $95 million. While the Nixon administration had asked for more funding—$150 million more for India, as well as $100 million more for Pakistan—the foreign aid bill had stalled in Congress. Even if the White House’s motive was to deny Gandhi a pretext for war, this U.S. assistance unquestionably saved many lives, and Nixon and Kissinger deserve real credit for that.

But this U.S. aid was overshadowed by something approaching ten million refugees. India was buckling under that burden, which cost far more than anything on offer from the United States, or any outside power. By a White House account, the expense of the refugees was by now roughly between $700 million and $1 billion annually—at least a sixth of India’s normal spending on development for its own people. To date, the United States had met perhaps a tenth of the cost of looking after the refugees for this year only, and the rest of the world had covered another tenth—leaving roughly 80 percent of the expense on poverty-stricken India. And this was at the peak of international concern for the refugees, before the world’s attention inevitably moved on to other matters, leaving India to cope alone.50

Before Gandhi’s arrival, the Nixon administration made one last push to get concessions out of Yahya—something that could put Gandhi on the spot when she showed up in Washington. Nixon wrote to Kissinger that there should be no pressure on Pakistan, only on India: “The main justification for some action on the part of Yahya, and I believe there is some, is that then we will be able to hit Madame Gandhi very hard when she comes here for her visit.”51

In mid-October, India’s complaints had reached a new crescendo after Pakistan started “a massive build-up” of troops, armor, and artillery on the western front, including Kashmir. India responded with its own deployment, leaving the two armies facing off. So the United States proposed a mutual withdrawal of Indian and Pakistani troops from the borders. Yahya gamely said he was willing to pull his troops and armor back. (The State Department noted with some jaundice that it was he who had first moved his troops to confront India.) As the summit approached, Yahya said that he would move first in withdrawing some of his troops, although wanting a promise from Gandhi to Nixon that she would soon follow suit.52

Gandhi shrugged this off. Indian officials protested that Yahya was trying to seem reasonable by undoing his own deployment, while Gandhi dismissed Yahya’s gesture as meaningless, complaining that he would withdraw on the West Pakistan front but not in East Pakistan, where the real danger was. More to the point, India knew just as well as the Americans how the military balance stood, and was not about to let Yahya off the hook. So India took a hard line, backing the Mukti Bahini and keeping the pressure building on Pakistan.53

WASHINGTON

Before Washington, Indira Gandhi stopped in New York, where she dazzled Hannah Arendt, herself a longtime critic of British rule in India. The political theorist breathlessly described Gandhi as “very good-looking, almost beautiful, very charming, flirting with every man in the room, without chichi, and entirely calm—she must have known already that she was go

ing to make war and probably enjoyed it even in a perverse way. The toughness of these women once they have got what they wanted is really something!”54

The Indian government was expecting a frosty summit. Kissinger warned Nixon that Gandhi was trying to set the president up, to claim that the Americans had driven her to war. The United States would help the refugees, Kissinger said, but would not help India wreck Pakistan’s political structure.55

“You know they are the aggressors,” Kissinger told the president, about the Indians. Briefing Nixon for Gandhi’s arrival, he assured him that Pakistan’s record was impressive. “I have a list for you of what the Pakistanis have done,” he said, “and really short of surrendering they’ve done everything.” (When he said that the United States had “stopped the military pipeline” to Pakistan, it came as a surprise to Nixon: “We have?”) Kissinger said that Yahya was willing to grant autonomy for East Pakistan, but blasted India for insisting that Yahya negotiate that with Mujib: “no West Pakistan leader can do that without overthrowing themselves.” By demanding Mujib’s participation, Kissinger said, the Indians were “in effect asking for a total surrender of the Pakistanis and that would mean to me that they want the war.”56

On November 4, Indira Gandhi arrived at the White House. From the welcoming ceremony onward, it was a disaster. Despite Kissinger’s reminders to Nixon to be on his best behavior in public, the two leaders, standing at attention on the South Lawn on a bright, crisp morning, were a portrait in sullen antipathy. They were visibly uncomfortable to be physically so close together. Gandhi, wrapped in a light orange overcoat against the autumn chill, glowered fixedly out from underneath her towering white-streaked coif. Nixon, his belly straining against his dark suit jacket, sported a particularly heartfelt version of his trademark scowl.57

Kissinger later wrote that Gandhi’s “dislike of Nixon” showed in her “icy formality.” Samuel Hoskinson, Kissinger’s aide, was struck by the tension and mutual loathing. “This was now between the heads of state who are deeply suspicious of each other,” he remembers. “He was the antithesis for her.” He says, “Shit, she thought this was the moment she was going to make history, destroy Pakistan entirely.”58

The state dinner went off miserably. There was an attempt at good cheer: a performance by the New York City Ballet; Pat Nixon draped in a floor-length gown of blinding 1970s cotton-candy pink; Gandhi only slightly less loud in a crimson sari with gold trim; and Nixon rather dashing in a tuxedo. But the president never enjoyed these functions at the best of times. He privately complained about the lack of patriotic spirit in the U.S. officials, with “only the shit-asses in the government” left unmoved by things like the Marine Corps Band. “The Congress, they sit there like a bunch of blasé bastards. They really do. The State Department people are horrible.” His main consolation was giving a genuinely delightful toast to Gandhi—composed, he said, without using anything prepared by the State Department, and delivered without notes, to dazzle the press corps with his grasp of foreign policy. He boasted, “I can do toasts and arrival statements better than anybody in the world. I have traveled all over the world.”59

But Gandhi and Haksar were left cold. The Indians were amazed that the president avoided mentioning the Bengali crisis in his toast. In hers, Gandhi made no attempt to charm. “Can you imagine the entire population of Michigan State suddenly converging onto New York State?” she asked. “Has not your own society been built of people who have fled from social and economic injustices? Have not your doors always been open?”60

Kissinger had more fun at the dinner. (“I liked the ballerina,” he told the president afterward.) But, chewing it over in the Oval Office the next morning, Nixon and Kissinger were both appalled by Gandhi’s toast. She “had gone on forever last night,” grumbled H. R. Haldeman, the White House chief of staff. Kissinger said, “The president made really one of the best toasts I’ve heard him make since we came here. Very subtle, very thoughtful, and very warm-hearted. Very, very personal. And she got up and—almost no reference to the president, somewhat friendly reference to Mrs. Nixon, launched into a diatribe against Pakistan, which, you know, it’s never done at a state dinner, that you attack another government.” (She had managed to avoid mentioning Pakistan by name, but had decried “medieval tyranny.”) Kissinger was put off by Gandhi’s mention of her democratic mandate: “Then she started praising herself, she said in effect that yes, this praise was well deserved, that I ran an election campaign.… And she said it was wrong to treat them the same way as the Pakistanis. Oh, it was really revolting, God.”61

On November 5, just before the Indian prime minister arrived at the Oval Office, Kissinger stopped by to give the president a final pep talk. He found Nixon already furious. The president said that the United States had given more relief aid to India than the rest of the world combined, and immediately exploded with rage, hollering, “Goddamn, why don’t they give us any credit for that?” Kissinger kept him boiling. “I wouldn’t be too defensive, Mr. President,” he replied. “Because these bastards have played an absolutely brutal, ruthless game with us.”

Kissinger laid out their actions that might mollify Gandhi: “famine relief, international relief presence, civilian governor, amnesty, unilateral withdrawal.” He said that the arms supply had dried up, while Nixon added that the Pakistanis had agreed not to execute Mujib, the Awami League’s popular leader. (Nixon asked, “what’s his name? Mujib? How do you pronounce?”) Kissinger said, “And also Yahya has said that he would agree to meet with a Bangladesh leader,” although not Mujib. “No,” said Kissinger. “No, no, no.” Meeting Mujib “would be political suicide for Yahya.” Nixon, aiming for a high tone, suggested telling Gandhi that while the Americans had no treaty with India, they were “bound by a moral commitment” to promote peace—and then snarled at Gandhi, calling her “the old bitch.”62

Kissinger urged Nixon to be tough on her. “I think publicly you should be extremely nice,” said the national security advisor—and at this point the tape is bleeped out, to hide whatever words he used to urge being rougher in private. Kissinger recommended sternly telling her that her Soviet treaty had cast doubt on India’s ostensible nonalignment, and that “a war with Pakistan simply would not be understood.”

Kissinger’s briefing set Nixon at ease. The president was impressed with what they had gotten the Pakistanis to do. Stumbling on the name, he said, “They’ve agreed not to execute Muju—Muju—however it is you say his name—” “Mujib,” said Kissinger. Nixon fluently rattled off Kissinger’s list of Pakistani concessions, such as a civilian governor and the unilateral troop withdrawal. The only options, the president concluded, were “accommodation or war,” and war would benefit no one. He was ready.

“I’m going to be extremely tough,” said Nixon.63

At last, away from the trappings and distractions of a state visit, Richard Nixon and Indira Gandhi faced off in the Oval Office. In an angry and protracted meeting, they grappled one-on-one, with only Kissinger and Haksar attending their chiefs. It was explosive. He thought she was a warmonger; she thought he was helping along a genocide. Summits are often pretty placid affairs, but this was a cathartic brawl, propelled not just by totally opposite views of a brewing war, but by the hearty personal contempt that the president and prime minister had for each other.

Nixon first emphasized U.S. aid to the refugees, but then sharply warned that launching a war was unacceptable. He said that the United States needed to maintain some influence with Pakistan, which explained a “most limited” continuation of military supply. Hitting his talking points, he recited the ways that the United States had ameliorated Pakistan’s positions: preventing a famine in East Pakistan, naming a civilian governor of East Pakistan, welcoming back refugees, talking to acceptable Awami League leaders, not executing Mujib, and now withdrawing some troops from India’s border. The United States could go no further. Gandhi listened, Kissinger later wrote, with “aloof indifference.” Nixon, refusi

ng to push for negotiations with Mujib, said that he “could not urge policies which would be tantamount to overthrowing President Yahya.”

India would win on the battlefield, Nixon said, but a war would be “incalculably dangerous.” With the superpowers involved on opposite sides, it would threaten world peace. Hinting broadly at a possible Chinese attack on India, he told the prime minister that a war might not be limited to only India and Pakistan.

Gandhi was blunter—if anything, less tactful than Nixon. Kissinger later wrote that her tone was that of “a professor praising a slightly backward student,” which Nixon received with the “glassy-eyed politeness” that he showed when trying to muscle down his resentment. She ripped into U.S. arms shipments to Pakistan, which had outraged the Indian people, despite her efforts to restrain her public.

She hammered away at Pakistan’s “persistent ‘hate India’ campaign,” which she blamed for the two previous India-Pakistan wars. Then she gave an expansive denunciation of Pakistan. Since its creation, it had jailed or exiled rival politicians. Many of its regions, like Baluchistan and the North-West Frontier Province, sought autonomy. (India, she claimed, had always shown some forbearance toward its own separatists—something that might have come as news to the Nagas and Mizos.) She blasted Pakistan’s “treacherous and deceitful” mistreatment of the Bengali people, and told detailed atrocity stories. She said that it was unrealistic to expect East and West Pakistan to remain united; the pressures for autonomy were too strong.

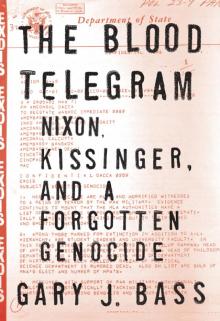

The Blood Telegram

The Blood Telegram