- Home

- Gary J. Bass

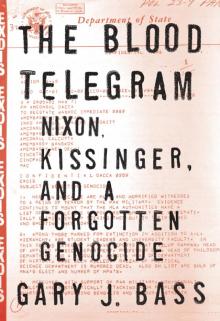

The Blood Telegram Page 16

The Blood Telegram Read online

Page 16

Jousting back, Archer Blood rejected that cringing tone. He warned that the carnage was driving moderate Bengalis into the arms of their leftist radicals, and that the Soviet Union had been more outspoken for human rights and democracy than the United States. On behalf of his whole consulate, he urged Nixon to tell Yahya of “our deep disapproval of suppression of democratic forces and widespread loss of lives and property.” He argued for cutting off U.S. military and economic assistance to Pakistan, urging a new “policy which freezes aid for the time being without apologetic statements and without utterance of hopes that US is desirous of resuming aid and anxiously awaiting G[overnment] O[f] P[akistan] plans.” Blood did not even trust Yahya’s government to deliver food aid, acidly noting that the military authorities’ “concern with food not convincingly demonstrated by continuing razing of markets.”11

From Delhi, Kenneth Keating similarly argued that the Nixon administration should exhort Pakistan to stop its repression and voice its “displeasure at the use of American arms and materiel,” which was proving hugely embarrassing. Keating wanted to stop U.S. military supply and suspend economic aid. He tried a realpolitik argument: “Pakistan is probably finished as a unified state; India is clearly the predominant actual and potential power in this area of the world.” Instead of backing a weak loser, the United States should turn to a strong winner.12

Rather than sticking up for his contrarians in Dacca and Delhi, the secretary of state tried to shut them up. Rogers told Kissinger, “We have Ken Keating quieted down.” Kissinger replied, “I appreciated that.” Thus the only diplomat whose opinion counted was Farland, whom Kissinger reached out to directly, bypassing the State Department, to ask the ambassador to send him a frank assessment.13

Farland decried the State Department’s advocacy for the Bengalis. Although admitting that Pakistan was crumbling, he still did not want to give up on it. The Pakistan army would soon wrap up its offensive and proceed to “mopping up,” which would get it out of U.S. newspapers. If the United States adopted Blood’s policy of leaning hard on Pakistan, Farland threatened to resign. In this private message to Kissinger, Farland slammed Blood: “Embassy has had full-scale revolt on general issue by virtually all officers in Consulate General, Dacca, coupled with forfeiture of leadership for American community there. Dacca’s reporting has been tendentious to an extreme.”14

The only really clear achievement of all this debate was to hurt Archer Blood’s feelings. He was lacerated to slowly realize that his fellow diplomats in Islamabad did not believe him. Despondent, evidently trying to salvage his career, he unconvincingly suggested that everyone—in Dacca, Islamabad, and Washington—was now on “approximately [the] same wave length,” and suggested that these matters were best “discussed over a drink with friends and colleagues.” Since he had just told his bosses that they were morally bankrupt and complicit with genocide, they might not have been inclined to invite him over for a beer.15

At an awkward meeting at the Islamabad embassy, Blood, along with Eric Griffel and Scott Butcher, held his ground, but found his fellow diplomats obviously saddened by them: Blood later wrote that “their formerly respected colleagues in the East Wing had clearly gone off the deep end.” When the deputy from the Islamabad embassy came to visit Dacca, downplaying the atrocities, an astonished Blood blew up at him. He hauled the visiting skeptic to Dacca University, showing him a stairwell that was heavily pockmarked with bullet holes. There was a sickly sweet reek from the bottom of the stairwell. They could make out rotting bodies. Blood’s colleague’s attitude had reminded him of Yahya’s reported response to the cyclone: “It doesn’t look so bad.”16

While the State Department was still busily honing its various arguments, Nixon and Kissinger could hardly have cared less. Pakistan’s role as a channel to China added to their unwillingness to speak up about the killings in East Pakistan. “Thank God we didn’t get into the Pakistan thing,” the president said. “We are smart to stay the hell out of that.” “Absolutely,” agreed Kissinger. “Now, State has a whole list of needling, nasty little things they want to do to West Pakistan. I don’t think we should do it, Mr. President.” Nixon growled, “Not a goddamn thing. I will not allow it.”17

ARSENAL AGAINST DEMOCRACY

The most neuralgic issue was U.S. military aid to Pakistan. As Blood persistently noted, Pakistan’s armed forces were using lots of U.S. arms against the Bengalis. He gave new specifics about the weapons—F-86 Sabre jet fighters, M-24 Chaffee tanks, jeeps equipped with machine guns—saying there was “no doubt” that it was happening.18

In early April, Kissinger’s staffers, Harold Saunders and Samuel Hoskinson, explained plainly what was at stake in continuing to arm Pakistan: “the rest of the world will assume—no matter what we might say—that we support West Pakistan in its struggle against the majority civilian population in the East. If we cut off their military supply or even suspend or slow it down, the West Pakistanis and the rest of the world will view it at a minimum as a move to dissociate ourselves and at a maximum as a move to halt the war.”19

By concentrating only on the question of what U.S. arms might now be shipped to Pakistan, the White House addressed only the smallest and newest part of the massive U.S. arsenal provided since the Eisenhower administration. Edward Kennedy’s office would calculate that 80 percent of Pakistan’s military equipment was from the United States, while the State Department rather fuzzily claimed that less than half of what Pakistan was currently using was American. Either way, it was a huge chunk of Pakistan’s total stockpile.20

But throughout the bloodshed, the White House did not make any complaints that Pakistan was using its current stores of U.S. weapons against the Bengali civilian population. Of course, even when Pakistani troops were not directly using U.S. tanks or warplanes, the presence of U.S. weaponry in other parts of Pakistan had the effect of freeing Pakistani troops up to mete out violence in East Pakistan. Still, the only weapons that the White House was considering were the latest installments of U.S. military assistance.

The White House struggled to figure out exactly how much weaponry was due to Pakistan. Samuel Hoskinson grimaces at the memory. “There was an endless debate about what was in the pipeline and what wasn’t,” he says. “We could never get a grip on it. It made you crazy. When you deal with the Pentagon, you go into a world of mirrors. It was a morass. Impossible to figure out.”

The details were confounding. Legally, Pakistan was still under a U.S. arms embargo, imposed after its attack on India back in 1965. But Nixon had opened up major arms shipments again in October 1970, when he had made an “exception” to the embargo, offering a big haul, hearkening back to the lavish period of U.S. weapons supply started under Dwight Eisenhower: armored personnel carriers, fighter planes, bombers, and more. None of this had been delivered yet, but Pakistan had put in a down payment for the armored personnel carriers, and was eager to get hold of the rest. Saunders calculated that Pakistan had some $44 million worth of military equipment on order from the United States, including $18 million of lethal arms, $3 million of ammunition, and $18 million of spare parts vital to keep the army and air force functioning. Kissinger somewhat more conservatively told Nixon that altogether, Pakistan was still awaiting delivery of some $34 million worth of military equipment, purchased over the past few years, although the real amount that would ship anytime soon would probably be half of that.21

This, Kissinger knew, would generate all the wrong kinds of headlines. The press was already in full cry over revelations that some ammunition and spare parts were still going out to Pakistan. Kissinger informed Nixon that “we have deliberately avoided” reimposing a total “formal embargo” on Pakistan. But they needed to avoid the embarrassment of major arms shipments to Pakistan at this moment. Through sheer good luck, it turned out that none of the major deliveries were scheduled during the crisis, which let the White House look less obdurate. As Kissinger told Nixon, if some spectacular U.S. weapons systems tur

ned up in Pakistan now, “the appearance of insensitivity” would provoke the Democrats who controlled Congress to legislate their own stop to arms shipments—which would be tougher than anything that the Nixon administration could contemplate.22

As the White House weighed its options, it did not realize that it had already been outmaneuvered by the State Department. Soon after the shooting started on March 25, the State Department had quietly imposed an administrative hold on military equipment for Pakistan, which was ostensibly only supposed to last until the White House could make a formal decision. The chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff said that the Pakistani military was “very bitter about the arms supply.”23

The result was a quiet suspension of the biggest shipments, like those three hundred armored personnel carriers and the fighter and bomber aircraft. Pakistan was still getting some U.S. supplies that were already under way. This was couched, Kissinger told Nixon, as “simple administrative sluggishness,” rather than a reprimand, because “we wanted to avoid the political signal which an embargo would convey.” Kissinger, evidently trying to drop a mollifying hint to Democrats, told McGeorge Bundy, the former national security advisor to John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, that there were a “few spare parts” on their way to Pakistan, but “nothing new is scheduled for shipment for six months or so. So we don’t have to face that for a few months. We’re going to drag our feet on implementing sales and drag out negotiations.”24

Kissinger was clear that neither he nor Nixon would support stopping arms supplies to Pakistan. This was merely a temporary, informal dodge, until the press found something else to write about. Those armored personnel carriers, for instance, were not due to be delivered until May 1972, and Kissinger, while deferring a decision about them, was not about to stop the sale or return the down payment. Kissinger suggested buying time on technical grounds. The deputy secretary of defense admitted that it was possible that some armaments would show up in Pakistan: “Congress may holler and you can just blame it on the stupid Defense Department.”

Some military supply would keep going. When it was pointed out that twenty-eight thousand rounds of ammunition and some bomb parts were due in July, and that Congress might object, Kissinger told a Situation Room meeting, “But we would pay a very heavy price with Yahya if they were not delivered.” He insisted that an explicit decision be taken by Nixon “before we hold up any shipments. This would be the exact opposite of his policy. He is not eager for a confrontation with Yahya.” Kissinger added, “If these weapons could be used in East Pakistan, it would be different”—although in fact the United States had not asked Pakistan to stop using tanks or warplanes against Bengalis.25

Nixon and Kissinger were pleased that the Pakistan army was regaining control of the scorched cities. In April, as his soldiers surged forward, Yahya tried to create a new government in East Pakistan to replace the elected leaders of the outlawed Awami League. He put forward Bengalis who were committed to a united Pakistan and disparaged the Awami League—in other words, the kind of people who had lost the elections. Blood laughed at Yahya’s docile group of collaborationist politicians, seen by the overwhelming majority of Bengalis as a “puppet regime.”26

Blood understood that this was only the first phase of a long civil war. The rebels, he reported, were avoiding direct clashes with the better-armed Pakistan army, to preserve their strength for later guerrilla combat. So the real war would come during the monsoon rains, as the fighting raged on in the countryside.27

The most surreal debate about who would win the civil war came when Blood, on a trip to the Islamabad embassy, had a face-off with, of all people, Chuck Yeager—the famous test pilot who had been the first human to break the sound barrier. Joseph Farland had somehow managed to enlist his fellow West Virginian, now a brigadier general, as a U.S. defense representative. By his own admission, Yeager knew almost nothing about Pakistan (a “very primitive and rough country and Moslem”), but quickly became a vehement supporter of Pakistan’s military.28

As Blood remembered, Yeager sneeringly asked him how the ill-equipped Bengalis could possibly stand up to the disciplined Pakistan army. Blood felt like snapping back, “Haven’t you fellows learned anything from Vietnam?” Restraining himself, he managed a suitably professional reply—that the guerrillas would wear down and outnumber the Pakistan army, and that India could quickly crush the Pakistan army too—but suddenly felt depressed and terribly lonely.29

Pakistan’s military advances throughout April reassured Nixon and Kissinger that Yahya might subdue East Pakistan after all. Alexander Haig, Kissinger’s deputy national security advisor—who would go on to be Ronald Reagan’s secretary of state—reassured Nixon, “The fighting is about over—there is considerable stability now.” Kissinger was bolstered by the CIA’s deputy director, who said that the Bengali rebels were collapsing. Heartened, Kissinger questioned the prospect of a long war. He admitted that if the Bengali nationalists launched mass noncooperation campaigns and marshaled guerrilla forces, the situation could prove “very tough,” but saw no evidence that they were doing that. Instead, he said, “West Pakistani superiority seems evident. I agree I used to think that 30,000 men couldn’t possibly subdue 75 million, which I suppose is the Western way of looking at it”—here he omitted his private discussions with Nixon, in which he had concluded quite the opposite. “But if the 75 million don’t organize and don’t fight, the situation is different.”30

Yahya was effusive in his gratitude to Nixon. In a warm letter, he sympathized about the American public pressure that Nixon was withstanding, and insisted that reports of atrocities were Indian-inspired exaggerations. He was “deeply gratified” that the United States saw the crisis as “an internal affair” to be resolved by Pakistan’s government.31

This was certainly Kissinger’s view. Even relatively minor insults to Pakistan’s sovereign prerogatives were too much for him. When it was suggested that Yahya promise that U.S. food aid would get to rural Bengalis, Kissinger recoiled at that “substantial challenge to the West Pakistan notion of sovereignty.” He said, “It would be as though, in our civil war, the British had offered food to Lincoln on the condition that it be used to feed the people in Alabama.”32

To others, Yahya looked a lot more like King George III than Abraham Lincoln. Keating, the ambassador to India, told a reporter that the concept of national sovereignty could be “overdone” (for which the State Department told him to shut up). And Blood and his consulate refused to accept that Yahya could do whatever he wanted within Pakistan’s sovereign borders, overturning a fair election and killing his citizenry. The “extra-constitutional martial law regime of President Yahya Khan is of dubious legitimacy (how many votes did Yahya obtain?).” They heralded the “anti-colonial” Bengali struggle, comparing it to the American Revolution. “They want to participate in deciding their own destiny,” Blood’s team wrote. “Even our forefathers fought for similar ideals.”33

There was another administration official with rather brighter career prospects who brought up human rights: George H. W. Bush, then the U.S. ambassador at the United Nations. The future president’s mission argued that India should be allowed to criticize Pakistan’s domestic human rights record at a United Nations body, because of the “tradition which we have supported that [the] human rights question transcend[s] domestic jurisdiction and should be freely debated,” notably Soviet and Arab oppression of Jews. “We have never objected to the right of others to criticize domestic conditions in the US maintaining that, as a free society, our policies are fully open to scrutiny.” That had the ring of principle, but Bush was not about to pick a fight with Nixon or Kissinger. Although he knew that something truly awful was happening in East Pakistan—his office had recently reported that the Indian government estimated the Bengali civilian death toll at between thirty thousand and a million, with the sober-minded Indian ambassador at the United Nations reckoning the total at roughly one hundred thousand—Bush made no effort to say a

nything beyond the official timid line of “concern” about the Bengalis.34

At the White House, Harold Saunders, Kissinger’s senior aide on South Asia, tried a somewhat louder—but still genteel—challenge to U.S. policy. Saunders remembers that he absorbed the angry complaints coming from the State Department, including those from Blood and others. “I was closely working with the people in State, who obviously were close to our people on the ground,” he says. “I realize how strongly they felt. And, I thought, with good reason. I agreed with them.”35

Saunders and Samuel Hoskinson argued that the Bengalis would almost certainly win, breaking free of a distant government in Islamabad with limited resources. The American public would recoil: a military regime was using mass killings to crush a majority that had won a fair election. Soon after, Saunders, appealing to Kissinger’s strategic sensibilities, tried out a realpolitik pitch for India: “Insofar as US interests can be defined simply in terms of a balance of power among states, it would be logical—if a choice were required—for the US to align itself with the 600 million people of India and East Pakistan and to leave the 60 million of West Pakistan in relative geographical isolation.” Kissinger was unmoved: “Whom are we trying to impress in East Pakistan?”36

On April 19, Saunders sent Kissinger a memorandum with the unusually intimate title “Pakistan—a Personal Reflection on the Choice Before Us.” Challenging Kissinger’s hope for Yahya’s military victory, he declared that the disintegration of Pakistan was inevitable. (This was confirmed by an intelligence community analysis, which said there was little chance that the army could put down the Bengali insurgency.) Saunders wanted to coax Yahya to pull back from a ruinous civil war, gently encouraging him toward autonomy for East Pakistan. Rather than threatening to cut off aid, as Blood would, he put his trust in Pakistani goodwill: “I would not tell Yahya that he must do anything.” This, he mildly wrote, would be merely “an effort to help a friend find a practical and face-saving way out of a bind.” In a joint paper with Samuel Hoskinson, he was somewhat more direct, saying that U.S. pressure could “preserve a relationship with Yahya while making a serious effort to get him—and us—off a disastrous course.”37

The Blood Telegram

The Blood Telegram