- Home

- Gary J. Bass

The Blood Telegram Page 14

The Blood Telegram Read online

Page 14

Gandhi declared that India had to resist such “injustice and atrocities,” and Indian officials in their private correspondence routinely referred to “Bangla Desh” instead of East Pakistan. But her government repeatedly batted away calls for recognizing Bangladesh as an independent state, which could easily ignite war with Pakistan. Privately, Gandhi worried that a great many Indians would take matters into their own hands.10

Inside and outside of government, Indians argued that Pakistan was finished. A senior Indian diplomat in Islamabad wrote that the army and the West Pakistani establishment could never win the loyalties of the East Pakistanis. The Indian diplomatic mission in Islamabad suggested that Pakistan’s military had decided that liberal and secular values in Bengali culture had become “an unacceptable threat to Pakistan’s Islamic ideology and to its existence.” For many Indians, the bloodshed showed a profound national crack-up in Pakistan—a historic failure of the ideal of Pakistan as an Islamic nation that united Muslims in both wings of the country. Haksar argued that Pakistan’s turmoil, pitting Muslim against Muslim, “clearly establishes the total inadmissibility of trying to found a nation on a religious basis.”11

From the start, the Indian press and Parliament ripped into the United States for supporting and arming Pakistan. Vajpayee urged the U.S. government to prevent Pakistan from using its weapons against the Bengalis, while one legislator said that the U.S. arms supply made it a “partner in genocide.” The U.S. consulate in Calcutta was swamped with petitions and pleas to stop arming the Pakistani military. The Motherland, a Jana Sangh newspaper, declared that genocide could not be seen strictly as an internal affair of Pakistan; the Hindustan Times asked why the United States would meddle in Soviet internal affairs to condemn the mistreatment of Soviet Jews, but stayed silent about the Bengalis; and the Times of India lambasted the United States for not warning Pakistan not to unleash U.S. arms against unarmed civilians. Hindi, Urdu, and Punjabi newspapers were even harsher. As the U.S. embassy in Delhi noted, the fire came from even the most pro-American publications. When the State Department claimed that it had no firsthand knowledge about Pakistani use of U.S. arms, it drew derision in the Indian press, which reported on Pakistan’s use of Sabre jets and M-24 tanks.12

Haksar wrote to a confidant that “our entire country is seething with a feeling of revulsion” at the Pakistan army’s actions. The government had to “reckon with it and deal with it, giving it some constructive direction. Prime Minister has been able to withstand the demand echoing from all the Legislatures in our land and from all our people to accord recognition to East Bangla Desh as a separate entity.” But there were demands that they give “the people of Bangla Desh … the necessary wherewithal with which to fight the bestiality of West Pakistan army. Many of the respected leaders of the people of East Pakistan have sent us appeals for help. We are in a terrible dilemma.”13

“Villages burn,” wrote a U.S. official traveling in the ravaged countryside of East Pakistan. “[W]e saw some burning Friday, villagers scurrying, bundles on their heads, children with suitcases, running, away, anywhere. Those that are fortunate have made it to India. Those that are rich have made it to the US or UK. The majority remain either waiting in their village for the attack to come, or living as refugees in the homes of Muslims, Christians, or other Hindus.”14

The refugees came on foot. Some of the luckier ones came by rickshaws, bullock carts, or country boats, streaming toward the safety of the Indian border. From the beginning, India kept its borders open to untold thousands of the dispossessed. “The flow of refugees was simply unstoppable,” recalled one of Gandhi’s top aides.15

The Indian prime minister’s secretariat knew that there was sure to be a rush of refugees, likely to overwhelm the local authorities in West Bengal. But the actual scale was a shock: the lieutenant governor of Tripura, an Indian state jutting deep into East Pakistan, alerted Gandhi to “the unexpectedly large influx of refugees.” As one of Gandhi’s senior aides remembered, her government now really began to worry. The expulsions seemed massive and systematic.16

It quickly became a human tide. By mid-April, there were more people than the stunned West Bengal government could possibly handle, necessitating help from Gandhi’s central government; by the end of April, Indian officials in Pakistan were estimating that nearly a million refugees had fled into India’s impoverished, volatile border states of Assam, Tripura, and, above all, West Bengal. India began setting up refugee camps in West Bengal.17

The refugees sharply ramped up the public pressure on Gandhi. From the border states, the Indian press reported in awful detail the exiles’ tales of shootings, rape, torture, and burning. There were renewed accusations of genocide, and overheated comparisons to the Holocaust.18

MRS. GANDHI’S SHADOW WAR

Indira Gandhi’s loyalists today often blame the war entirely on Pakistan. K. C. Pant, a young minister of state for home affairs in 1971 who went on to become Indian defense minister, recalls, “There was no, as far as I know, no intention to provoke a war, or to create a situation where war became inevitable. That was not the intention at all.” But in fact, Gandhi’s government was planning for war from the start, and escalated toughly as the crisis wore on.

As early as April, India’s government was bracing for a military confrontation. Some Indian hawks were tempted to strike while Pakistan’s rulers were still in panicky disarray. Several of Gandhi’s ministers demanded that the army march into East Pakistan; she was under tremendous public pressure, particularly from the Jana Sangh; and some Indian advisers were urging the government to seize this opportunity.19

Just over a week after Yahya’s crackdown began, the top echelon of the Indian government—including Haksar and the foreign and defense ministers—received a brilliant and brutal argument for war from K. Subrahmanyam. (He also published a truncated newspaper version, which scandalized Pakistan.) As the director of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, an illustrious think tank funded by the defense ministry, Subrahmanyam was well launched on a career that, over six decades in public life, would make him India’s most influential strategic thinker.20

Subrahmanyam secretly urged the government to swiftly escalate the crisis all the way to war, establishing Indian hegemony over all of South Asia. The Bengali guerrillas, he argued, would not be able to defeat the Pakistan army, and anyway he doubted that India could avoid directly fighting Pakistan. Pakistan’s “military-bureaucratic-industrialist-oligarchic” rulers, he argued, might actually prefer to spark a war with India and lose, rather than face the bigger humiliation of defeat by Bengali people power. India’s armed forces, he confidently predicted, would quickly win a two-front war, capturing East Pakistan while fighting hard against West Pakistan.

The world would accept India’s fait accompli, he claimed. The United States had gotten away with its interventions in Guatemala and Cuba, and the Soviet Union with its in Hungary and Czechoslovakia. Despite China’s bitter rivalry with India, he doubted that China would really ride to Pakistan’s rescue. With Pakistan ripped apart, India would dominate South Asia. And Subrahmanyam saw the strategic uses of moralizing: if India could make “the Bangla Desh genocide” its cause for war, then the superpowers—and even revolutionary China—would find it hard to support Pakistan.21

Gandhi took an early decision for war. “I knew that the war had to come in Bangladesh,” she later told a friend. Major General Jacob-Farj-Rafael Jacob, the chief of staff of the army’s Eastern Command, remembers getting marching orders at the beginning of April. “This was her orders,” he says. “Then I get a phone call from Manekshaw”—the top officer, General Sam Manekshaw, the chief of staff of the Indian army—“telling me to move in.” But India’s generals balked at the unfavorable conditions for combat. Jacob recalls, “I tell him, no way. I told him that we were mountain divisions, we had very little transport, we had no bridges.”22

The military, according to its top ranks, persuaded Gandhi to wait awhile

. The rivers and swamps of East Pakistan were daunting terrain. “There were a lot of tidal rivers to cross,” says Jacob. “The monsoon was about to break. If we moved in, we’d get bogged down. We need bridges and time for training. I told Manekshaw this. I sent a brief, which he read out to Mrs. Gandhi. He asked the earliest I could move, and I said the fifteenth of November. This was conveyed to Mrs. Gandhi, who was wanting us to move in immediately, and she accepted that.”23

At the time, Manekshaw told General William Westmoreland, the U.S. Army’s chief of staff, that the Indian military had sobered its hawkish civilian politicians, who were eager to strike in East Pakistan. Since then, he has recounted a detailed story of military caution similar to Jacob’s. In Manekshaw’s flavorsome and well-polished version—which has taken on a halfway mythological character in Indian military circles—in April, as the refugees flooded in, Gandhi angrily waved a telegram from the chief minister of one of the border states and, in front of her cabinet, asked him, “Can’t you do something?” Manekshaw replied, “What do you want me to do?” “Go into East Pakistan,” she said. “This would mean war,” he replied. “I know,” Gandhi reportedly said. “We don’t mind a war.” But the general balked. “In the Bible,” he claims to have said, “it is written that God said, ‘Let there be light, and there was light.’ You think that by saying ‘Let there be war,’ there can be a war? Are you ready for a war? I am not.”24

Manekshaw says that he explained to the cabinet that the imminent monsoon would make ground operations impossible, and the air force could not provide support in awful weather. Two divisions were nowhere near East Pakistan. His armor was underfunded. China could strike in defense of Pakistan. So he recommended postponing the war until winter, when snow on the Himalayan mountain passes would freeze out Chinese troops. “If you still want me to go ahead, I will,” he reportedly told an unhappy Gandhi. “But I guarantee you a one hundred per cent defeat.” Jagjivan Ram, the defense minister, urged him to act. He refused. Gandhi, fuming and red-faced, dismissed the cabinet, holding Manekshaw behind. He offered his resignation. In his account, he told her, “Give me another six months and I guarantee you a hundred per cent success”—unusually cocksure stuff for a professional soldier speaking to a civilian commander. Gandhi put him in charge. “Thank you,” he purportedly said. “I guarantee you a victory.”25

Until the weather changed, India had another military option: helping to support a Bengali insurgency against Pakistan.

Yahya’s slaughter drove Bengalis to take up arms. The nucleus of the resistance was trained Bengalis serving in Pakistan’s military, in units called the East Pakistan Rifles and the East Bengal Regiment, as well as police officers. Unable to stomach the crackdown, many of these Bengalis rebelled. They became early targets for Yahya’s assault. As Archer Blood remembered, the Pakistan army “deliberately set out first to destroy any Bengali units in Dacca which might have a military capability,” particularly the Bengali troops in the East Pakistan Rifles. “And so they just attacked their barracks and killed all of them that they could.” Scott Butcher, the junior political officer in the U.S. consulate in Dacca, says that the Pakistan army swiftly turned on the Bengalis in their ranks: “a lot of the gunfire we heard were executions of some of those personnel.” Some of these Bengalis reportedly killed their own West Pakistani officers and ambushed other army units.26

As Indian diplomats in Pakistan reported, “Heavily armed military columns with devastating fire power and air support were used against the Freedom fighters and civilians in mopping up operations in the countryside and along the border with India.” The Bengali insurgents—known first as the Mukti Fouj (Liberation Brigade), and later as the Mukti Bahini (Liberation Army)—fought back with attacks on roads and bridges. Pakistan, Indian officials thought, aimed to wipe out the guerrilla resistance before the monsoon season—or to drive them into India. “We are just waiting for the monsoon,” said a Bengali rebel. “We are masters of water.”27

One powerful Indian official, D. P. Dhar, the ambassador in Moscow—a confidant of Gandhi’s who was well known as part of the “Kashmiri Mafia”—wanted India’s paramilitary forces to arm these rebels with artillery and heavy mortars from the start. Writing to his close friend Haksar, Dhar argued that “our main and only aim should be to ensure that the marshes and the quagmires of East Bengal swallow up” Pakistan’s military. He hoped that “in the not very distant future the West Pakistan elements will find their Dien Bien Pho in East Bengal. This will relieve us of the constant threat which Pakistan has always posed to our security directly and also as a willing and pliable instrument of China.” He urged Haksar, “This resistance must not be allowed to collapse.”28

It was not. With extraordinary swiftness and maximum secrecy, India backed the rebellion—although the army worried about how Pakistan and China might react. India, which vocally advocated national sovereignty, would be embarrassed to be caught stirring up rebellion inside Pakistan. But as early as March 29, K. F. Rustamji, the famed police officer leading India’s Border Security Force, was allowed to offer limited help to the Bengali rebels. After Parliament’s bold resolution against Pakistan on March 31, Rustamji claims that Indira Gandhi privately told him, “Do what you like, but don’t get caught.”29

According to Rustamji, Gandhi herself met with Bengali leaders in the first week of April, as they were establishing their guerrilla force. On April 1, as a top secret Indian memorandum shows, two senior Bengali nationalist leaders met with the Indian government, with the Indians desperately trying to keep it secret. The Bengalis (“our Friends”) had plenty of manpower, but would need some “training in guerilla tactics, to prepare for a long struggle.” India would provide “material assistance,” likely including arms, ammunition, organizational advice, broadcast and transit facilities, and medicine. The Border Security Force would be the main agency in charge of these operations, but the Indian army might have to get involved too.30

This effort embroiled the highest levels of the Indian government and army. Gandhi, gravely worried about her government’s new responsibilities, created a special committee on East Pakistan and the insurgency, including Haksar, the foreign and defense ministries, and R. N. Kao, the head of the R&AW spy agency, sometimes calling in General Manekshaw. At Gandhi’s command, political talks with “the leaders of the Bangla Desh movement” went through “the secret channels of the R&AW.” Haksar, fretting that the R&AW’s normal spy duties were getting swamped, obliquely noted that the intelligence agency was now running “the special operations which have become necessary.”31

India worked closely with the self-declared Bangladeshi government in exile, which was allowed—despite bitter protests from Pakistan—to set itself up on Indian soil in Calcutta. There Rustamji and General Jacob coordinated their efforts with Tajuddin Ahmad, the Bangladeshi prime minister. Keeping the R&AW in the loop, Rustamji and Jacob planned camps where the Indian army would train Bengali nationalist guerrillas, cooperating with Bengali rebel commanders on tactics. According to Jacob, the Border Security Force launched an unsuccessful raid inside East Pakistan.32

Gandhi was fully in the loop. In mid-April, Kao told the prime minister that “the [Pakistan] Army is planning to move towards the Indian border in order to cut off the main supply routes for the Liberation Forces.” And according to Haksar’s notes, Gandhi was to tell opposition lawmakers that India was spending about $80 million that year on the insurgency, and that the “burden for sustaining the fight of the people of Bangla Desh” cost as much as providing for the refugees.33

This exile government announced on April 17 a proclamation of independence for a sovereign democratic republic of Bangladesh, accusing Pakistan of genocide. The Border Security Force set up the event just inside East Pakistan. Gandhi still held back from recognition, withstanding the public uproar in India, but her government secretly offered them “all possible help” and assisted in keeping the guerrilla war going. India asked the Bangladeshi authoritie

s to keep a lower profile in Calcutta and, behind closed doors, urged them to make their joint strategy appear to be the plan of the provisional government.34

India avidly worked to keep the rebellion in the control of pro-Indian and relatively moderate Awami League nationalists, fearing Bengali extremists who were more pro-Chinese. Haksar, disheartened that Mujib and his fellow Awami League politicians had been taken by surprise by Pakistan’s onslaught, now worried at the “total absence of central political direction to the struggle inside Bangla Desh.” This sustained guerrilla war, Haksar thought, would require leadership from the fledgling Bangladeshi government.35

Rustamji was impressed with the insurgents’ fighting spirit. They toasted together to “Bangla Desh.” But the Bengali fighters expected India to go to war almost immediately, and were crushed when they realized that was not in the offing. The Border Security Force was frustrated too, but Rustamji says that General Manekshaw warned him that his covert activities could easily lead to war, and India was not ready for that yet.36

The Indians and Bengalis secretly worked hand in glove on guerrilla warfare, on everything from recruitment (Rustamji favored university graduates) to blowing up bridges (which Tajuddin Ahmad wanted to do without hesitation even if it angered locals). The Indian army suggested targeting the Pakistan army’s heavy reliance on petrol. Tajuddin Ahmad asked for medical aid, credit, and radio transmitters aimed at Dacca, all the while urging India to recognize Bangladesh.37

The Indian army too had its orders. By his own account, General Sam Manekshaw, the Army Chief of Staff, decided to have the Indian army train and equip three brigades of regular Bengali troops, drawing mostly on defectors from Pakistan’s East Bengal Regiment and the East Pakistan Rifles. In addition, Manekshaw wanted to train and arm about seventy-five thousand guerrillas. Manekshaw would later frankly admit to Soviet military chiefs that India had given “all possible help in the organisation, arming and training of the Freedom Fighters.”38

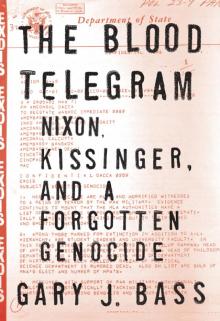

The Blood Telegram

The Blood Telegram