- Home

- Gary J. Bass

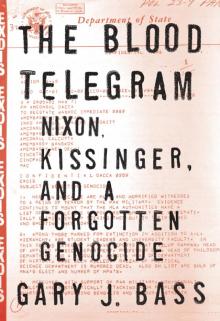

The Blood Telegram Page 10

The Blood Telegram Read online

Page 10

Although he was low in the hierarchy of decision making, Blood proposed reversing Nixon and Kissinger’s policy of acquiescent silence. He saw no point in covering up the bloodshed, or in denying that the Dacca consulate was relaying detailed accounts of the slaughter—even though he knew that that would expose the consulate, and would presumably result in Pakistan expelling him from the country. “Full horror of Pak military atrocities will come to light sooner or later,” he wrote. Instead of pretending to believe Pakistan’s falsehoods, he wrote, “We should be expressing our shock, at least privately to G[overnment] O[f] P[akistan], at this wave of terror directed against their own countrymen by Pak military.”30

Blood and some of the other Americans had been hiding Bengalis from the Pakistan army. In this cable, he now admitted this to his superiors: “Many Bengalis have sought refuge in homes of Americans, most of whom are extending shelter.”31

He later wrote that “virtually all Americans in Dacca, official and unofficial, had terrified Muslim and Hindu Bengalis hiding in their servant quarters. As far as I know, these refugees were poor and apolitical. My own servants were sheltering a number.” He admired his servants’ compassion and was not about to stop them. Blood later said:

We were also harboring, all of us were harboring, Bengalis, mostly Hindu Bengalis, who were trying to flee mostly by taking refuge with our own servants. Our servants would give them refuge. All of us were doing this. I had a message from Washington saying that they had heard we were doing this and to knock it off. I told them we were doing it and would continue to do it. We could not turn these people away. They were not political refugees. They were just poor, very low-class people, mostly Hindus, who were very much afraid that they would be killed solely because they were Hindu.

Meg Blood knew that her diplomatic residence was supposed to be immune to the army. She remembers that the servants’ quarters were behind the main houses, behind the gardens, meaning that they could give shelter without being conspicuous. “They didn’t stay too long,” she says. “They would go on to their own families. They would go over the walls, into neighbors’ servants’ quarters, and were sheltered that way as they kept out of sight.”32

Before the crackdown, there had been a friendly group of Bengali policemen camped out in tents in the Bloods’ front yard. On the bloody night of March 25, they realized that armed Bengalis would be shot on sight, so they buried their rifles in the Bloods’ lawn, ditched their uniforms, and blended in with the servants. They later escaped. One corporal later turned up at the Bloods’ house, asking Archer Blood to drive him in to the military authorities and vouch for him as trustworthy. Blood anxiously did so, and believed that the policeman was not harmed.33

Not everyone protected Bengalis. Scott Butcher did not, although he heard about other Americans who did. He remembers a young professor’s wife coming to his house. “She prostrated herself at my wife’s feet and said, ‘You must help us, you must help us.’ It was pretty unnerving.”

Eric Griffel recalls that some Americans sheltered Bengalis knowingly, but says that he did so without being aware of it. “You never really knew who lived in your quarters,” he says. “I did find out that there were some relatives of some of my servants who hid out. Muslims. I wasn’t surprised when I did find out.” The West Pakistanis, he says, were already “angry at the local Americans, because their attitude was perfectly obvious. Private citizens, journalists, missionaries—pretty well all of them were sympathetic to the Bengalis.”

Desaix Myers, a young development officer working for Griffel, was single then and had a four-bedroom apartment in a pleasant neighborhood. “I had a couple in my house,” he says. He put up curtains to hide these Bengalis from view. Some of them were students at Dacca University, friends of his, who asked if they could stay there after the army stormed the campus. His cook moved in his whole family. “There must have been six or seven in the servants’ quarters,” Myers says. “Everyone was a little worried. We didn’t know what was going to happen.” Was he afraid that the Pakistan army might be angry at him? “We were young and invincible.”

To Blood’s surprise and relief, his shocking “selective genocide” cable won a prompt endorsement from Kenneth Keating, the U.S. ambassador in Delhi.34

Keating was not someone who could be easily dismissed. He was a formidable political figure in his own right: a former Republican senator from New York. In his early seventies, he had a weathered handsomeness, with bright blue eyes, bushy gray eyebrows, and a full shock of elder-statesman white hair; he had served in both World Wars, leaving the army as a brigadier general, with a military bearing to match. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, he had amazed all of Washington by mysteriously managing to find out about the Soviet missiles placed in Cuba six days before John Kennedy did—and announced it from the Senate floor, to the president’s humiliation and rage. (Kennedy had despondently said, “Ken Keating will probably be the next President of the United States.”) But the Kennedys had gotten their own back when Robert Kennedy swept into New York and knocked Keating out of his Senate seat. In consolation, Nixon appointed him ambassador to India. Sydney Schanberg remembers him as an old-fashioned conservative, a moderate Rockefeller Republican. Schanberg liked him: “He was very undiplomatic.”35

As the shooting started, Keating was near the end of his career and his life, unafraid to speak his mind. In Delhi, he absorbed the outrage of Indians there. Major General Jacob-Farj-Rafael Jacob of the Indian army recalls, “Keating agreed with me entirely.” The general remembers Keating turning red when asked why the United States was supporting Pakistan despite the atrocities. Thus Keating became an outspoken advocate for both India and the Bengalis, repeatedly lending his own gravitas and respectability to the Dacca consulate’s dissenters. “Bless him,” says Meg Blood. “He was strongly for us.”36

When Keating saw Blood’s cable, he immediately backed it, firing off an equally furious cable of his own with the same jarring subject line of “Selective Genocide.” He wrote, “Am deeply shocked at massacre by Pakistani military in East Pakistan, appalled at possibility these atrocities are being committed with American equipment, and greatly concerned at United States vulnerability to damaging allegations of associations with reign of military terror.” The ambassador—making a complete break with U.S. policy—urged his own government to “promptly, publicly and prominently deplore this brutality,” to “privately lay it on line” with the Pakistani government, and to unilaterally suspend all military supplies to Pakistan. He urged swift action now, before the “inevitable and imminent emergence of horrible truths and prior to communist initiatives to exploit situation. This is [a] time when principles make [the] best politics.”37

Keating made sure that news of the killings would get out. “He would drop me information from time to time,” remembers Schanberg. “Stuff that I would have no way of knowing.” Schanberg, returning to Delhi after being thrown out of Dacca, had emotionally told Keating in detail about what he had witnessed. Keating now fed to Schanberg a story for the New York Times recounting a “massacre.” Schanberg says, “Keating was really mad. That’s why he was giving stuff out.” The article angered the Pakistani government and U.S. officials, but Keating unrepentantly took full responsibility for the leak. He defiantly told the State Department, “I know of no word in the English language other than massacre which better describes the wanton slaughter of thousands of defenseless men, women and children.”38

Keating also tried to appeal to Nixon’s and Kissinger’s pragmatism. If Pakistan fell apart, as seemed likely, the United States would want to be on decent terms with a new Bangladesh; if Pakistan somehow held together through sheer brutality, it would be shaky and weak, with far less “geopolitical importance” than India. But he was muzzled by the State Department, not even allowed to offer a wan public expression of sympathy for the Bengali victims.39

Keating was not the only ambassador who seemed to have gone local. The U.S. ambassador to Pakista

n, Joseph Farland, proved to be a vehement supporter of Yahya’s government.

Farland had almost flawless conservative credentials: a Republican lawyer from West Virginia who had served at the FBI and then as ambassador to the Dominican Republic and Panama. (One flaw: attending four Communist Party meetings while in college.) He did not enjoy living in South Asia and had little curiosity about the region. Once, he crudely explained to Nixon and Kissinger that “this problem goes back to about the year AD 712, when the Muslims first invaded the Sind. There’s been no peace on the subcontinent since that time because the Hindus and the Muslims have nothing in common whatsoever. Every point of their lives is diametrically opposed—economic, political, social, emotional, despite their beliefs. One prays to idols, the other prays to one God. One worships the cow; the other eats it. Simple as that.” (Nixon had his usual Pavlovian reaction to the mention of India: “Miserable damn place.”)40

“He was almost a caricature, I thought,” remembers Eric Griffel, the insubordinate development chief in Dacca. “Wealthy West Virginia lawyer, bright enough, complete lack of knowledge about the subcontinent, and not interested in world politics.” Farland once visited one of Griffel’s development projects, a dry dock called Roosevelt Jetty. “Roosevelt Jetty?” asked the Republican ambassador. “Theodore,” Griffel quickly replied.

Farland was Blood’s immediate superior, even though the Islamabad embassy was a thousand miles away from Blood’s consulate in Dacca. Blood was wary of Farland’s chummy ties with Yahya, who often drank with him or took him on shooting excursions. Blood thought that the relationship between his consulate and Farland’s remote embassy was wretched.41

The official view from Pakistan’s military rulers was simple: the atrocity stories were fabrications, and Pakistani unity would be restored in a matter of days or weeks. As Yahya wrote to Nixon, East Pakistan “was well under control and normal life is being restored.” There was no mention of the violence in the press, which was censored under martial law.42

Still, the Islamabad embassy did not really believe that this violence would succeed. Even Farland deplored “the brutal, ruthless and excessive use of force by Pak military.” The Bengalis, he wrote, would not “accept rule by bullet.” But unlike Blood and Keating, he stuck to U.S. policy. After reading Keating’s cable about “Selective Genocide,” Farland frostily informed him, “Intervention by one country in the internal affairs of another tends to be frowned upon.”43

Throughout West Pakistan, many other U.S. officials were outraged at the atrocities. From Lahore, the U.S. consul cabled a report that there was a “veritable bloodbath taking place in East Pakistan with literally thousands already slain.” There was enough protest among U.S. officials across Pakistan that Farland had to warn his staffers in Karachi, Lahore, and Dacca to “not r[e]p[ea]t not voice opinions or pass judgments on the army intervention in East Pakistan.” U.S. diplomats should instead affect “an unemotional, professional attitude.” Farland squelched their humane instincts: “Regardless of our personal feelings, what has happened is strictly an internal affair of Pakistan’s about which we, as representatives of the US G[overnment], have no comment.” He invoked diplomatic duty: “Since we are not only human beings but also government servants, however, righteous indignation is not itself an adequate basis for our reaction.”44

Trying to muzzle Blood, Farland granted that his Dacca officials were having “a most difficult and personally trying time,” but reminded him to ensure that his officers maintain the “discretion” expected of U.S. diplomats. Blood and his team bristled. “In a country wherein our primary interests [are] defined as humanitarian rather than strategic, moral principles indeed are relevant to issue,” he retorted to Farland. “Horror and flouting of democratic norms we have reported is objective reality and not emotionally contrived.”45

At the White House, Blood’s anguished “selective genocide” message jolted Kissinger’s expert on South Asia, Samuel Hoskinson. Kissinger himself was reading the cable traffic, sometimes quite closely, but if he had somehow missed it, Hoskinson promptly alerted his boss: “Having beaten down the initial surge of resistance, the army now appears to have embarked on a reign of terror”—here he repeated Blood’s phrase—“aimed at eliminating the core of future resistance.”

Hoskinson put Blood’s call for new policies directly to Kissinger: “Is the present U.S. posture of simply ignoring the atrocities in East Pakistan still advisable or should we now be expressing our shock at least privately to the West Pakistanis?” Hoskinson explained that Blood wanted to complain to Yahya’s regime, and backed up Blood: “The full horror of what is going on will come to light sooner or later.” And ongoing U.S. aid to Pakistan could be seen as a “callous” endorsement of Pakistan’s actions.46

But Nixon shrugged off the accumulating alarms from Blood, Keating, and Hoskinson. When Kissinger brought up the slaughter in East Pakistan, Nixon refused to say anything against it: “I wouldn’t put out a statement praising it, but we’re not going to condemn it either.”47

“I DIDN’T LIKE SHOOTING STARVING BIAFRANS EITHER”

Rather than being appalled by the ferocity of the crackdown, Kissinger—when speaking only to Nixon—was impressed. He thought it could work.48

This, remembers Hoskinson, was “a bit of wishful thinking, combined with a lack of knowledge of the Bengali drive for nationhood. Plus tough talking from the West Paks: ‘We can handle this. We’re supplied by you, we’ll put this down, not to worry.’ ”

On March 29, Kissinger told Nixon, “Apparently Yahya has got control of East Pakistan.” “Good,” said the president. “There’re sometimes the use of power is …” Kissinger completed the thought: “The use of power against seeming odds pays off. Cause all the experts were saying that 30,000 people can’t get control of 75 million. Well, this may still turn out to be true but as of this moment it seems to be quiet.”

Nixon turned philosophical, pondering the uses of repression: “Well maybe things have changed. But hell, when you look over the history of nations 30,000 well-disciplined people can take 75 million any time. Look what the Spanish did when they came in and took the Incas and all the rest. Look what the British did when they took India.” “That’s right,” Kissinger concurred.

Far from Dacca, Nixon and Kissinger hovered comfortably at the level of academic conceptions. “But anyway I wish him well,” Nixon continued about Yahya. “I mean it’s better not to have it [Pakistan] come apart than to have to come apart.” He said, “The real question is whether anybody can run the god-damn place.” Kissinger, sympathizing with Yahya’s difficulties, said, “That’s right and of course the Bengalis have been extremely difficult to govern throughout their history.”49

Kissinger’s hope that the Bengalis could be pounded into submission lingered for several weeks. Pakistani military officers assured the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff that they could prevail. “All our experts in the Pentagon and elsewhere were dead sure that West Pakistani military forces could not overpower the people of East Bengal,” Kissinger told the Indian ambassador in Washington, “but it seems they have done so. What options do we now have? We must be Machiavellian and accept what looks like a fait accompli—don’t you think?”50

Samuel Hoskinson, Kissinger’s staffer, remembers that Blood’s cables got no leverage in the White House—even though the CIA chief in Dacca admired Blood’s coolness in terrible circumstances, and Hoskinson’s friends in the Foreign Service held Blood in high regard as a reporter. Hoskinson says, “We’d call them to the attention of Henry and Haig. It didn’t seem to get a lot of response in policy terms.” He notes about Blood, “He was regarded as being squishy. Maybe a little bit too enamored with the Bengalis and their leadership, a little soft-headed on this stuff.”51

Blood, he recalls, was “worrying about the plight of the Bengalis, which they didn’t give much credence to. Human rights didn’t really count for much.… You don’t get down and wallow around in this

stuff. We’ve got American interests on the line there. That’s the mind-set.” He says, “In retrospect I think he had it about right. But he didn’t have the credibility. There was always the tendency to believe more what was coming from Islamabad.… And we got this bleeding heart out there in Dacca.”

Hoskinson remembers, “There was a disconnect between the bureaucracy, even the NSC staff, and the thinking of Kissinger and the president.” Trying again, he urged Kissinger to reconsider his refusal to criticize Yahya despite Blood’s reports of “widespread atrocities by the West Pakistani military.” Hoskinson and another White House aide pointed out that both Blood and Keating wanted the United States to distance itself from the killings, with Keating warning about the risk of the United States being associated with “a reign of military terror.”52

But Kissinger only paid enough attention to Blood’s cables to mock him for cowardice. “That Consul in Dacca doesn’t have the strongest nerves,” Kissinger told Nixon. “Neither does Keating,” said the president. “They are all in the middle of it; it’s just like Biafra. The main thing to do is to keep cool and not do anything. There’s nothing in it for us either way.” Nixon said, “What do they think we are going to do but help the Indians?” Kissinger agreed: “It would infuriate the West Pakistanis; it wouldn’t gain anything with the East Pakistanis, who wouldn’t know about it anyway and the Indians are not noted for their gratitude.”53

Despite the United States’ considerable influence on Yahya, Kissinger said, “In Pakistan it continues, but there isn’t a whole lot we can do about it.” He assured Nixon that they were not pressuring Pakistan. The president said that “we should just stay out—like in Biafra, what the hell can we do?” (Neither of them noticed that the United States was actually thoroughly involved, taking Pakistan’s side.) “Good point,” Kissinger replied. Nixon said, “I don’t like it, but I didn’t like shooting starving Biafrans either.”54

The Blood Telegram

The Blood Telegram